New illustration class is creating a graphic anthology in one term

Isaac Peterson’s students have 10 weeks to create a 100-page graphic anthology. Every Friday, the Art 199 Illustration class meets for 5 hours of lecture, discussion, one-on-one and group work with Peterson, an art professor at Central Oregon Community College. Genres range from office comedy to urban fantasy to Biblical interpretations, and styles run an even wider gamut. The Broadside interviewed Peterson to find out why one professor and a small group of students would try to complete such a Herculean task.

Broadside: Who was behind the genesis of the Illustration class?

IP: I asked Bill Hoppe to give me a 199 class in narrative illustration and I was very nervous it wouldn’t fill because it was a special section. I made some posters and hoped for the best, watching the numbers slowly increase between quarters. When I had 12 I felt satisfied andstopped watching it, but on the first day I was shocked to find 24 students! Some people dropped but it is still a big class and has the most incredible work energy. I met Tony Russell, who teaches writing, and discovered he’s teaching a Graphic Novels as

Literature course so there has been a certain synchronicity. I’ve been teaching art for 15 years and I’ve never had a course with such incredible positive energy. It is electrifying. The class is 5 hours long and I was worried it would be exhausting, but it goes by too fast and everyone wants to keep going.

Broadside: What does a class day look like? Is there any instruction or is

it all drawing and hands-on work?

IP: Each class starts with a student presentation on a comic book

artist or children’s book illustrator. In addition to giving some

bio and showing the artist’s work, students also have to create

a drawing lesson for the class. Even though these lessons are

just small details, learning a single tool in drawing can

transform your entire style. This is followed by one of my

lessons on drawing or structuring narrative. This week we are

studying how to create ink textures. The rest of the class is one

on one and group work where we all draw together and discuss

and edit the structure of each story’s narrative. I’ve had some

incredible guest artists show their work in the class. Donald

Yatomi, the lead concept artist at Sony Playstation/ Bend Studio

took us through his creative process in fine detail. Students

were speechless — no one knew a world-class game studio

existed in Bend, first of all, and the simplicity and utter

creativity of Yatomi’s concept art blew us all away. I think in

that one moment, student perception of art practice suddenly

shifted from “silly hobby” to “possible future career.”

Broadside: What are some common challenges you see your students

working to overcome?

IP: Narrative illustration means that storytelling comes first

and that the images serve the story. Artistic ambition can

sometimes work counter to story telling! Some students fret

over small details — a tree doesn’t look the way they want it

to, their anatomy isn’t as good as it could be, etc. The first

thing we do is mock up the story with stick figures, and I say,

“Your story made me laugh when it was just stick figures!” The

primary rule of narrative illustration is not to stop the story for

any reason. Don’t give yourself an excuse to stop! Finish the

story and leave the mistakes in it. We are asking: “What story

do you really want to tell?” and that is a surprisingly intense

question. The answer truthfully communicates the feelings and

experiences of the story teller, even if it emerges in the form

of science fiction. It’s easy to look for little reasons to stall the

story, in particular saying the art isn’t good enough. But often

these are excuses created to stop the story from emerging

because it is so meaningful to them that they are afraid of

telling it.

Broadside: What is some of the literature that students draw inspiration

from, if you all talk about inspiration? (Being a graphic novel

nerd myself, I’m keen on some name-dropping.)

IP: Each week there is a presentation on a narrative artist. We

study Moebius, Mo Willems, Maurice Sendak. We also focus on

local Oregon independent cartoonists such as Matt Wagner and

Portland’s Dark Horse Comics. A major focus of the course is

giving illustrators their due and discussing some of the terrible

injustices wreaked upon visual creators. Siegel and Shuster,

creators of Superman, received a pittance from DC comics

rather than the royalties they deserved, and Jack Kirby, the co-creator of what are now multi-million dollar properties such as

The X-Men, The Avengers, Thor and Iron Man never saw the

profits of his creations. We also study forgotten masters such

as Kay Neilson, a masterful illustrator who created the definitive

images for Hans Christian Anderson (the movie Frozen is based

on his illustrations), and the original illustrator of the Wizard

of Oz, W.W. Denslow. The creator of Popeye, E.C. Segar, is

a veritable fountainhead of creative innovation who created

visual and cultural templates which persist today, but we don’t

remember their origin (for instance, he invented the word

“goon”).

Broadside: You all set out to put together an anthology in ten weeks. How’s it going? Does it look like you’ll reach your goal?

IP: Oh my goodness, this class has been a tsunami of creativity. I

can’t believe the incredible things students pull out of the air

every week, and the incredible scope of their vision. I look

forward to learning more about their characters each week and

get so excited to see the new pages. As of this week (week

six) I’d say we have about 40 pages as a group, and I think by

the end of class we might have about 75. I’m lucky to have a

studio assistant, Marcy, who scans all of our work at the library

each week and sends it to Dropbox. Then together we bring

the scans into InDesign and assemble and rearrange the book.

We will release the finished product on CreateSpace, a publishing service owned by

Amazon, so anyone will be able to buy it when it is

finished. All I can say is this has been the best class I’ve ever

had in 15 years of teaching, and my students’ infectious energy

has me staying up every night working on my own comics as

well.

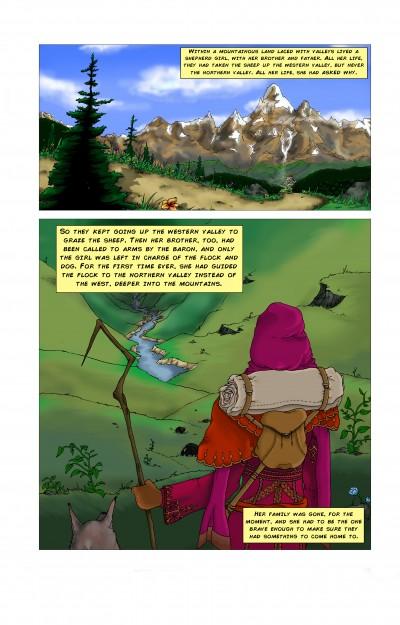

Kiley Christiansen

Christiansen’s grandmother is faculty at COCC; she saw a flier for the graphic novel class and thought Christiansen would be interested in it. Christiansen has had this story idea floating around in her head for over a year.

Christiansen has been drawing for a very long time and mostly draws the things she sees in her head, only using the occasional model for anatomical reference.

“Originally, I thought it would be more of just written-down word,” Christiansen said, “but I had all these images in my head and I just thought it would be just a shame not to put them down in ink and pen.”

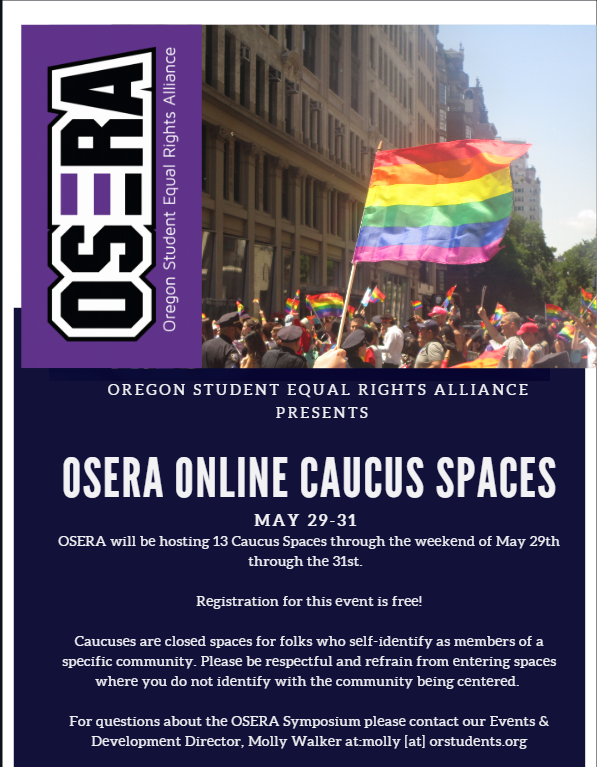

Cecelia Kirth

Kirth gets ideas for stories all the time, but this was one that stuck. For Kirth, who won the Best in Illustration award at the annual COCC student art show this year, it’s a matter of getting the ideas down on paper.

“Even if I only get a tiny part of it, I’ll come back to it and remember,” Kirth said. “I have a lot of ideas riding around all the time through my head.”

Kirth will be graduating after fall term, and intends to keep illustrating as a hobby but isn’t interested in publishing her work as more than that.

Josh Bickford

Bickford is adapting a friend’s novel to graphic form, a process which presents it’s own unique challenges.

“Some parts are pretty difficult,” Bickford said. “I’m definitely having to switch around some of the dialogue where there’s a lot of description. It’s a lot of manipulating that to work better in the comic panel forms.”

But with unique challenges come unique opportunities, and Bickford has had lots of fun designing characters for the story.

“I enjoy comics and I wanted to do something more with drawing, but maybe not the classic style that the other classes offer currently,” Bickford said.

Scott Greenstone

Student interviews by Stewart Shaw

The Broadside