Defending a man that I hate – or, at least, his right to free speech

Over the past two weeks, I have watched our community react to the Charlie Hebdo attacks, and the attacks on the Paris kosher butcher store. I asked students in my history classes what their immediate reactions were. I heard a host of responses, ranging from self-blame (it’s our fault for not being more tolerant of Muslims), to blaming Islamic civilizations since the Middle Ages (they took Constantinople in 1453, and here they are again, taking more). I also spoke to a local news anchor, whose sole purpose was to show how innocent “Islam” was, to show that the doctrine of Islam did not call for violence. Still, she did not report on the longer history of Islamist violence, its provenance, and the historic tensions between Algerians and the French nation—which has everything to do with politics, and nothing to do with religious doctrine. She did not want to hear my condemnation of the attacks, my concerns about anti-semitism, and the loaded history of colonization that lurked behind the Kouachi brothers’ mass murder.

All of these community opinions mirror the larger debates, which also swing drastically from one extreme to another:

-Bill Maher and his atheist followers would like to blame the entirety of “religion” for the attacks.

-Others hold Israel responsible for provoking waves of Islamist violence by angering “the Muslims.”

What’s troubling about all of these reactions, to me, is that they don’t hold the individual criminals accountable. It reminds me of the way that the public New York intellectual Hamid Dabashi reacted when his friends asked him about the September 11th attacks the day after they occurred:

“Why would I have any privileged access to the mind of a criminal who had just blown up two beautiful towers in our city? … It never occurred to me on April 19, 1995, when I heard about the Oklahoma city bombing, to find a colleague and ask him, “Why would they do something like that?”

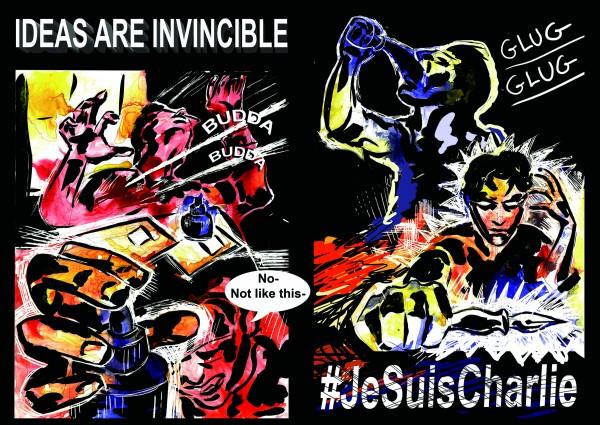

Such is the trouble. We are stuck in a mire of questions with no moral outlet. Even the unifying #jesuischarlie twitter movement for unadulterated free speech has been exposed as biased. When the vindictive and nasty comedian who calls himself “Dieudonné” (meaning god-given) facebooked “je me sens Charlie Coulibaly,” or I feel like Charlie Coulibaly, meaning he was offering support to the murderer who had killed four people in a kosher grocery shop the day before. Even as new #jesuischarlie cartoons were appearing and days after an international cohort marched in Paris defending free speech, Dieudonné was condemned for his flagrant free speech.

To get to the bottom of this, it’s important to understand the legalities dictating so-called free speech—“blasphemy” is not legally reprehensible, because of the anti-clerical roots of modern France. As France struggled to become a democracy, it was important to revolutionaries to undermine the historical power of the Catholic Church. Hence, Charlie Hebdo’s possibly blasphemous depictions of Muhammad and the Pope are not illegal. On the other hand, it is illegal to incite discrimination or violence toward a particular ethnic group—and this was what Dieudonné was accused of doing toward the Jewish victims.

So what is the answer? How to possibly balance individual criminals within the undeniable larger trend toward Islamist violence? This is the true puzzle. Democracies that were born in the 18th century (France and the United States) have always endured this challenge. How to let the population be free, while also addressing the common good? Where is the line between individual sovereignty and the power of what Jean-Jacques Rousseau called the general will?

Apart from the subversive artists of Charlie Hebdo, another victim has emerged as a symbol of the many dueling questions at the center of this heartbreaking attack. The Twitter hashtag #je suis Ahmed honors the Muslim policeman, Ahmed Merabet, who arrived at the scene of the Charlie Hebdo crime, and was killed with the others. Free speech has a right to be offensive. My favorite tweet of recent weeks says it all:

Dyab Abou Jahjah ( @Aboujahjah) wrote, “I am not Charlie, I am Ahmed the dead cop. Charlie ridiculed my faith and culture and I died defending his right to do so. #JesuisAhmed”

As Jahjah attests, hating someone’s message does not justify violence. An offensive comment demands a defense, a condemnation, but an arrest? It’s too much, especially given the public outcry for free speech.

So, here is how I end up defending a bigoted comedian that I hate—Dieudonné should not have been condemned. Because, if “I am Charlie,” then “I am also Dieudonné.” Yes, Dieudonné, the comedian who makes Holocaust jokes, the one who joked he felt like the murderer. People like him make democracy and free speech difficult and uncomfortable. But no one said it was supposed to be easy.

Jessica Hammerman | COCC Professor