Human Immunodeficiency Virus swept through America in the 1980s, creating in its wake confusion and fear. There was little known about this infection beside the wildly inaccurate stereotypes, which were especially harmful when so many lives were affected.

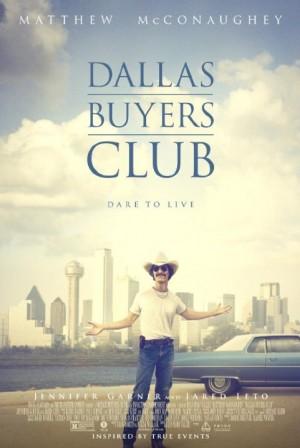

Dallas Buyers Club, starring Matthew McConaughey and Jared Leto as his transexual business partner, tells the story of Texas outlaw Ron Woodroof and his fight to bring unapproved medicine to AIDS patients in 1985. Told by his doctors upon being diagnosed HIV-positive that he had only thirty days to live, Woodroof began receiving AZT, an antiviral and the only treatment at that time for the AIDS virus, by bribing a hospital worker. Nearly dying from the combination of AZT and cocaine, Woodroof travels to Mexico to speak with Dr. Vass, who has had his American medical license revoked. Dr. Vass prescribes Ron a combination of ddC and the protein peptide T, both of which are not approved by the FDA, and which Dr. Vass claims are better options to AZT. Because the drugs are not illegal but only unapproved, Ron begins selling these drugs to AIDS patients on the streets of Dallas. Partnering with Rayon (Jared Leto), Ron starts a buyer’s club for these unapproved medicines. Charging $400 a month, HIV-positive members are given drugs that are an alternative to the untested AZT that is still in its trial period.

Matthew McConaughey and Jared Leto lost a combined weight of over eighty pounds for their roles in this movie. To see Leto’s character Rayon shakily pull off her dress to see her withered and emaciated body, ravaged by AIDS and spotted with lesions, is painful to watch. The dedication to the story is visible in all the actors. Steve Zahn as a local Dallas police officer with a father suffering from Alzheimers shows the dichotomy of the situation; enforcing the new FDA law against the use of unapproved drugs while employing Woodroof’s peptide T to help his father.

The movie, directed by Jean-Marc Vallée, was above all else, a character study. Ron Woodroof’s transformation from a spitting homophobe to his acceptance of the very people that he is helping is mesmerizing to watch. Director of Photography Yves Bélanger shot the movie beautifully, capturing the people and the locations where the movie took place. Writers Craig Borten and Melisa Wallack kept the story alive with captivating dialogue, combining humor with biting reality. And the reality is that the viewer is watching people die.

What the movie had in performance, it lacked in pace. Often times I felt suffocated in a scene. Things moved languidly in the movie, which often proved as no form of forward movement in the story. Woodroof managed to survive seven years after his HIV-positive diagnosis but the viewer had no handle on such a thing as time in this movie. The movie could very well have taken place inside a six month period.

There is a generational gap within this movie’s ability to be understood. To millennials, the HIV virus is mostly seen as a devastating infection and not a reason for ostracization. The stigma put onto AIDS patients is virtually extinct with the understanding that we now have on the infection. The same was not true for those alive during this new epidemic. Fear was widespread as the disease was unknown and proved lethal. This movie showed how little sympathy was given to those suffering. A sense of that shame and stigmatizing is perhaps lost on a lot of the younger audience.

Cooper Malin

The Broadside

[email protected]