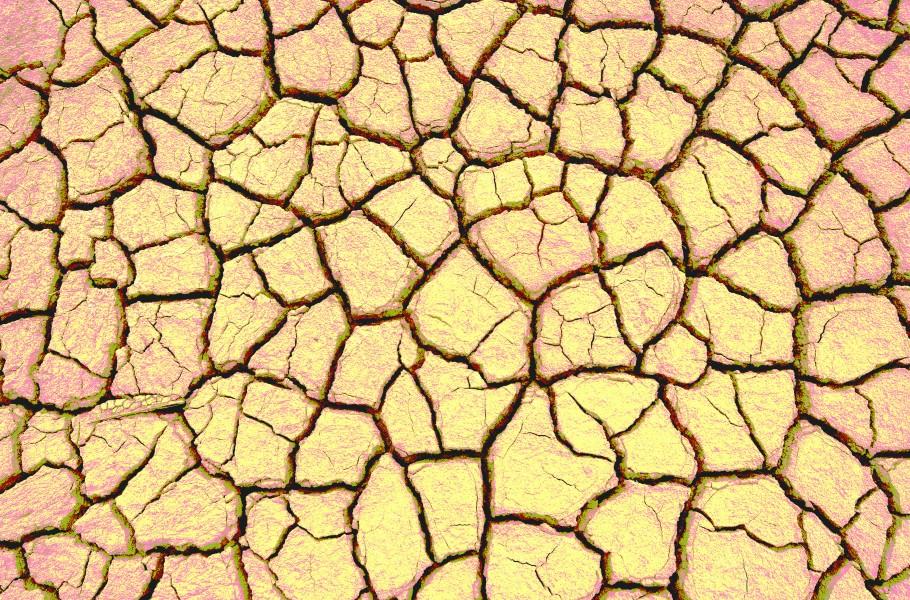

What will the drought mean for Central Oregon?

January 2015 marked the warmest winter on record

for Oregon since record taking began in 1895,

according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Association.

California isn’t faring any better with 2015 showing

to be the driest on record prompting Governor

Jerry Brown to sign the “first ever statewide mandatory

water reductions,” according to the state’s

website ca.gov. This comes a year after Governor

Brown declared a State drought emergency last year

in January of 2014.

While Oregon State does not have the magnitude

of agriculture that California does, parts of Oregon’s

economy is heavily based on agricultural products.

West of the Cascades, in the Willamette Valley vegetables,

tree fruits, berries, hazelnuts, wine grapes,

hops, diary, and timber are the region’s staple crops,

whereas alfalfa, hay, garlic, and beef cattle make

up Central Oregon’s most profitable agricultural

products, according to Oregon Department of Agriculture.

While Deschutes County has not been

hit as hard by the drought, Oregon’s Governor Kate

Brown signed a drought state of emergency for

neighboring Crook County on April 7.

“[The drought] will certainly affect farmers on

the West side more than it will affect farmers on the

East side in the beginning because the West side,

like the Willamette Valley, is much more reliant

upon snowmelt-fed streams, such as the Willamette

or the McKenzie. The Deschutes is driven largely

by stored water in the aquifer,” said Ron Reuter,

associate professor of natural resources at Oregon

State University-Cascades, who teaches soil science

and ecology.

The aquifer in Deschutes County gets refilled

from both precipitation and snowmelt unlike the

aquifers West of the Cascades that rely solely on

snowpack. As long as we are getting a normal

amount of rainfall, those aquifers can recharge,

Reuter added. “In California they’re in the middle

of probably what is going to be a 10 year

drought,” Reuter said. “They’re reliant, just like

the Willamette Valley on snowmelt getting into

their aquifer, which they don’t have the snow to

get that water in there.”

There are other problems associated with the

water depletion from the aquifer.

“Water is non-compressible, so its actually

holding up a lot of that land area, and what they

are finding is that with aquifer depletion, when

you take that water out you are getting land settling,”

Reuter added.

Effects on wildlife habitats

Another effect of the drought, are the impacts

on wildlife habitat, including those on fish life,

and micro-invertebrate (insects) populations.

“For fish it means the stream temperatures are

likely to get warmer and [possibly] too warm for

fish earlier in the season than they typically do,”

said Lauren Mork, monitoring coordinator for the

Upper Deschutes Watershed Council.

One of goals of The Upper Deschutes Watershed

Council is to monitor stream temperatures

for the Deschutes River, Tumalo Creek and

Whychus Creek, to determine if stream temperatures

are too high for survival of native fish species

including trout, and whether restoration is

needed.

Temperatures are expected reach above 18 degrees

Celsius this year, which is the biological requirement

for trout, rearing and migration. When

temperatures exceed 18 degrees trout cannot grow

or thrive and will even die if the temperatures get

high enough, added Mork.

“This year we are at around five percent snowpack

in the Cascades, that will affect stream flow

particularly on creeks that don’t have reservoirs

Stream flow is diverted for irrigation on the Deschutes,

Tumalo Creek, and Whychus Creek,”

Mork said.

On the Deschutes River there are reservoirs that

are actually full because we did receive enough

precipitation. On Tumalo Creek and Whychus

Creek where there aren’t reservoirs, we will only

have what is currently stored in snowpack.

The Deschutes River Conservancy is one nonprofit

organization that works to restore stream

flow and increase water quality in the Deschutes

Basin.

“One thing we have seen over the years, as

stream flow restoration has occurred the microinvertebrate

community has become characterized

by species that prefer cooler temperatures, so we

are actually seeing them respond to temperatures

coming down with increased flows,” Mork said.

Michael Gary | The Broadside

(Contact: [email protected])