Scott Greenstone

The Broadside

The Freedom Rides of 1961 weren’t the first time Claude Liggins was discriminated against on public transit.

When Liggins was in his mid-teens, he decided to sit on the white half of a Lake Charles, La. bus. After telling Liggins he would call the police, the bus driver pulled over at a service station. The black half was full of people telling Liggins to get off.

“Tears were beginning to come from my eyes. I heard the voices in the back telling me to leave,” he said. “I heard my own voice telling me to stay.”

The only other person in the white half was a woman, who Liggins remembers clearly through the commotion. She said, “He has a right to be here.”

Out of fear, Liggins got off the bus.

“I cried all the way home. I told myself I would never move again,” said Liggins. “It made me a stronger person.”

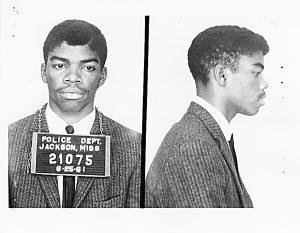

On June 25, 1961, a “nervous and scared” 20-year-old Liggins boarded the train for Jackson, Miss. He was soon after arrested and sent to Parchman Penitentiary with hundreds of other Freedom Riders.

Liggins says that his Freedom Ride started long before the day he got on the train to join the West Coast Freedom Riders.

When Liggins was four, he went into town with his grandmother, who gave him a quarter and told him to go buy a candy bar. He decided to buy a hamburger instead, and went into a white-only cafe. He was told to stand up against the wall while the cook prepared the hamburger, and Liggins said even then he knew he was being treated unfairly.

“I never forgot that, and today as I look back on it, I say ‘that was my first sit-in,” said Liggins.

When Liggins moved from Louisiana to Los Angeles, it was 1959 and he was 19, going to school full-time and working full-time at night. In 1961, he heard about the Freedom Rides while he was riding the bus home from work. He said to himself, “I should’ve been part of that.”

Liggins soon contacted the Congress of Racial Equality’s office in Los Angeles, but because of his young age, they were reluctant to let him go.

“I told them I was going even if I had to follow them,” said Liggins.

Soon, he had completed the nonviolence training mandatory for Freedom Riders in New Orleans and was on his way to Jackson, Miss., where Freedom Riders were being arrested and sent to the state’s notorious Parchman Penitentiary.

“By the time that I got there, there were three people in a cell,” said Liggins. “We had filled the jails in Jackson.”

The Freedom Riders kept their spirits up by singing, until their mattresses were taken and away and they were put in a place called the Hole. In the Hole, fifty or sixty Freedom Riders were shoved into a small space.

“Like a can of sardines,” said Liggins. “It reminded me of what it must have been like to be a slave on a ship, all stuffed down in the bottom, all chained up.”

Liggins was released from Parchman after 43 days and continued aiding the civil rights movement.

Today, Liggins sees immigration as one of the Freedom Ride-worthy issues. “Everybody wants the opportunity to help support their families. I don’t know why we can find a thousand ways to hurt a person but cannot find a couple ways to help some people.”

Liggins points back to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, and especially the man who stood in front of the tanks. “That kind of bravery, that he was able to make those tanks move a little bit–those are the kinds of things that people should look at and put themselves in these people’s shoes and understand that they’re just like you. They want the same things that you want.”

Liggins hopes that for the people he shares his story with, Bend will be where their Freedom Ride begins.

“I’m hoping that when people meet me, and I tell my story, I’m hoping that somebody would be like I was… ‘I want to do something. I want to help change the world.’”

(Contact: [email protected])