Black culture is always being put under a microscope. A couple months ago, a white comedian, Andrew Schulz, disparaged Black music after insulting and disrespecting Black women on a podcast with Black men. This criticism isn’t always unwarranted, but it is tiring because no matter the disdain, Black culture is American culture.

Ranging from the way that people talk, to the music they listen to–even the way they dress. What was Hamilton inspired by? Hip-Hop. It’s no secret as to why Black Panther remains one of the highest grossing movies of all time. And the Super Bowl halftime show, which rakes in astounding viewers each year, usually does so because it celebrates Black culture. Who were the progenitors of rock & roll but Chuck Berry and Little Richard?

Even objects perceived as truly American culture have close ties to Black Americans. Who invented a staple of country music, the banjo, but enslaved Africans? Black culture is all around us, but still somehow obstinately refuted. People instead belittle what they don’t understand. In short, Black culture is put under a microscope and a platform simultaneously.

This contradiction is always brought to the forefront when Black History Month comes around, and each year my ambivalence emerges. Words cannot encapsulate the gratitude I feel, the pride for having my people recognized for an entire month, I’ll confess. To receive even a modicum of the respect we deserve and all too brief appreciation. But why must our history, American history, be relegated to one month of the year? Black History deserves to be taught year round–it needs to. Without African Americans there would be no America, so why do we get tossed to the wayside?

In the years preceding college, only during the month of February are we taught about the same figures: Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman, maybe even Frederick Douglass. Malcolm X would get a name drop, if you’re lucky. Every single one of these people left their own indelible marks on history that can never be understated. But what about the hundreds of named and unnamed figures never given the laurels they deserve?

Civil rights and women’s rights activist Dorothy Height, who helped organize MLK’s March on Washington. Fifteen-year-old Claudette Clovin, the Rosa Parks before Rosa Parks, performed the same action in the same city, mere months prior. The pioneering abolitionist and journalist Ida B. Wells who analyzed the sociological force behind lynching and widened public awarness of it.

I love being a Black American. I love knowing my history, but I’ve had to excavate for my history. I have to dig and scavenge for what should be common knowledge. Beginning at the foot of an intimidating mountain of history, the broadest search engine on Earth, Google, was my guide. Article by article I learned, researching song lyrics, watching and reading documentaries, all to educate myself. That’s not counting what history I’ve learned from my mentors as well. In short, I’ve had to get my history from far too many sources out of my own initiative.

Here I arrive at the core of this piece; my conflicted emotions regarding Black History Month. I’m grateful that we have something like this to celebrate every year, that it gets half as much attention as it does. That so many organizations and schools take part in it nationwide.

But at the same time, for the longest time, I spent every February learning about the late great MLK and four others. After a while I just began to feel frustrated. Not just because of how much more there is to Black activism in the 50s and 60s but the redundancy of it all. It’s frustrating to never feel like I’m making progress in learning.

A pivotal moment, one I’ll never forget, was in my sophomore English class. Malcolm X was once again glanced over in the second month of the year. At last I asked my teacher: “Why can’t we learn about people like him?” Her response was: “Too controversial.” In private, she told me about the school board’s insistence on stagnation; the regulation of history.

Exacerbating my anger, I must admit that I began to feel resentful toward Martin Luther King Jr.–representing everything wrong with the education system. Not fair, I know. But it wasn’t simply because he was championed by the white man for his peaceful tactics. It was combined with the lack of teaching that, following the assassination of the radical Malcolm X, King, too, became more radical.

In 1967, mere months before his assassination, King began planning the Poor People’s Campaign. In his own words it was simple: getting the poor people of America to march to Washington D.C., to force the federal government to pass what King had called an economic bill of rights. Stamped from the Beginning, by Ibram X. Kendi, states the loose conditions King laid out: “Full employment, guaranteed income, and affordable housing…a bill that sounded eerily similar to the economic proposals on the Black Panther Party’s ten-point platform.”

These blatant exclusions reflect the outright refusal to add more to the narrative of a God-loving American proposing peace over violence. The Civil Rights Movement would not have been possible without the likes of Martin Luther King Jr., no. But it was the combined efforts of people like him and Malcolm X who preached of justice “by any means necessary,” in addition to the many others acting in this same period. In addition to those who preceded them, including many courageous and amazing women who have been essential to the progression of African Americans.

The Civil Rights Movement activist who is famously attributed to the quote, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired,” Fannie Lou Hamer, has been left out for decades, despite her accomplishments. She was among the first three women to stand in the U.S. Congress in 1964, founded the National Women’s Political Caucus, and much more.

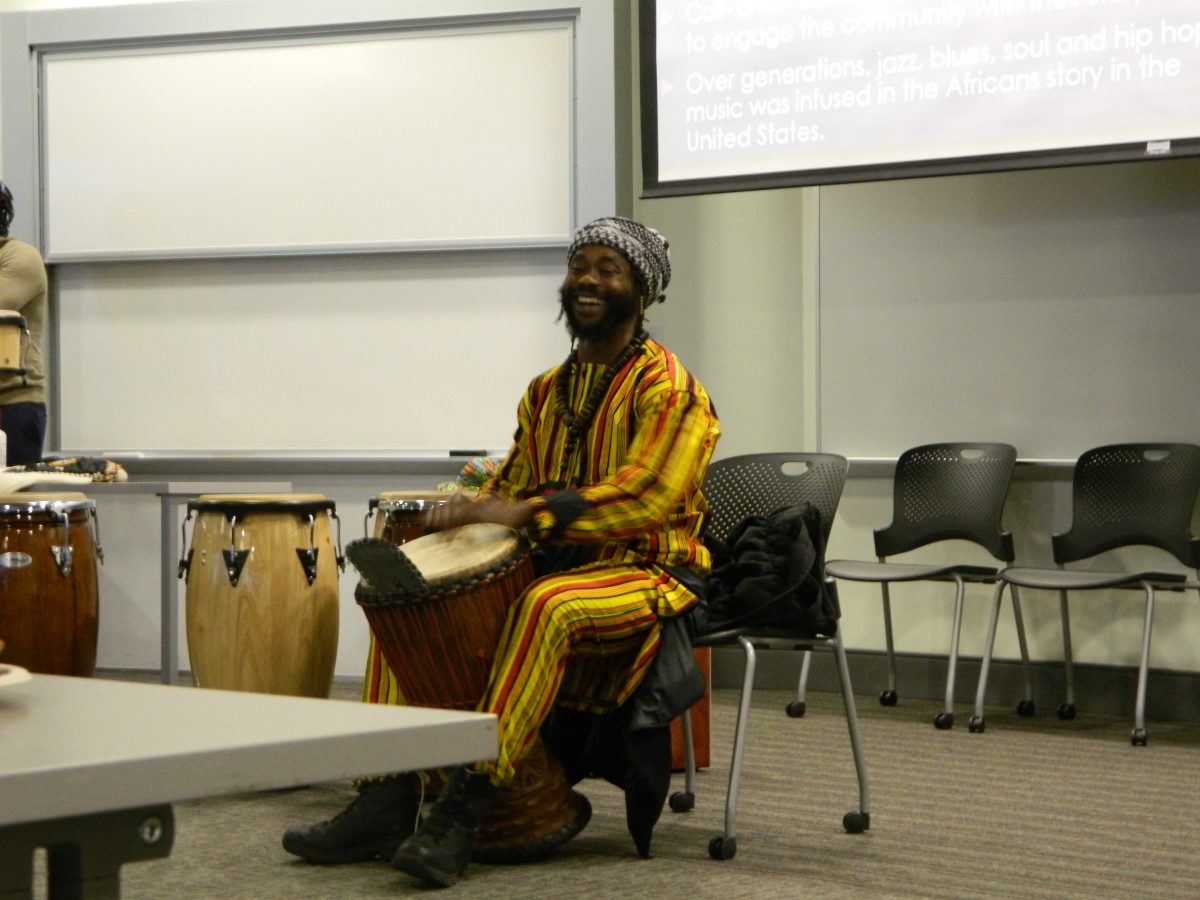

It’s difficult to draw the line between the bitterness I feel toward the education system and my ambivalence regarding Black History Month, because for most of my life they were one and the same; only learning about Black history in February. Only now, attending an institution of higher education, am I able to see much more variety in how Black History Month is celebrated. Central Oregon Community College featured a litany of events; the daughter of Desmond Tutu as a guest speaker, a movie screening and discussion thereafter, and a Black dinner/celebration to bookend the month.

It’s refreshing. But my vexation hasn’t completely faded.

It remains unfair that Black history is taught as specific events on a specific month. So much remains untaught. Only a few years ago I learned that Rosa Parks was actually planted on that Montgomery bus in 1955. She was working with her local NAACP chapter. She wasn’t simply someone who remained seated out of happenstance as the history books would have you believe, no. She was part of an orchestrated plan to destabilise the status quo.

It leaves me wondering: why? Why paint such a disingenuous picture of a pivotal moment in history? Perhaps to lessen her impact, to obfuscate the fact that this decision was intentional, not simply born from weariness or anger with American society in 1955. By teaching a sanitized version of events, we are diminishing heroes like Rosa Parks. By creating the arbitrary barrier between American history and Black history, yes, we may have a temporary spotlight, but we lessen the importanceof these American heroes, relegating them to the ensemble and not the main cast.

The pride I feel for my culture far outweighs any negative emotions I may hold. No matter what happens in our country, this shall never change. I only hope that more people will seek out more history for themselves. Spend just a couple minutes looking into the history of the inventions they use, to see for themselves the unseen Black influence. Delve into the meaning of the lyrics and learn about the artists who wrote them. Make the choice to learn about the richness of true American history, beyond what is taught.