The Bend City Council made an ambitious goal of building 1000 affordable housing units across 2 years; a rate five times the amount of affordable housing units built in previous years. The council is hopeful this will ease the housing predicament Bend is going through.

Lynne McConnell, Housing Director of the Bend City Council spoke with The Broadside to explain Bend’s unique situation, as well as steps toward improvement and ways people of the community can help.

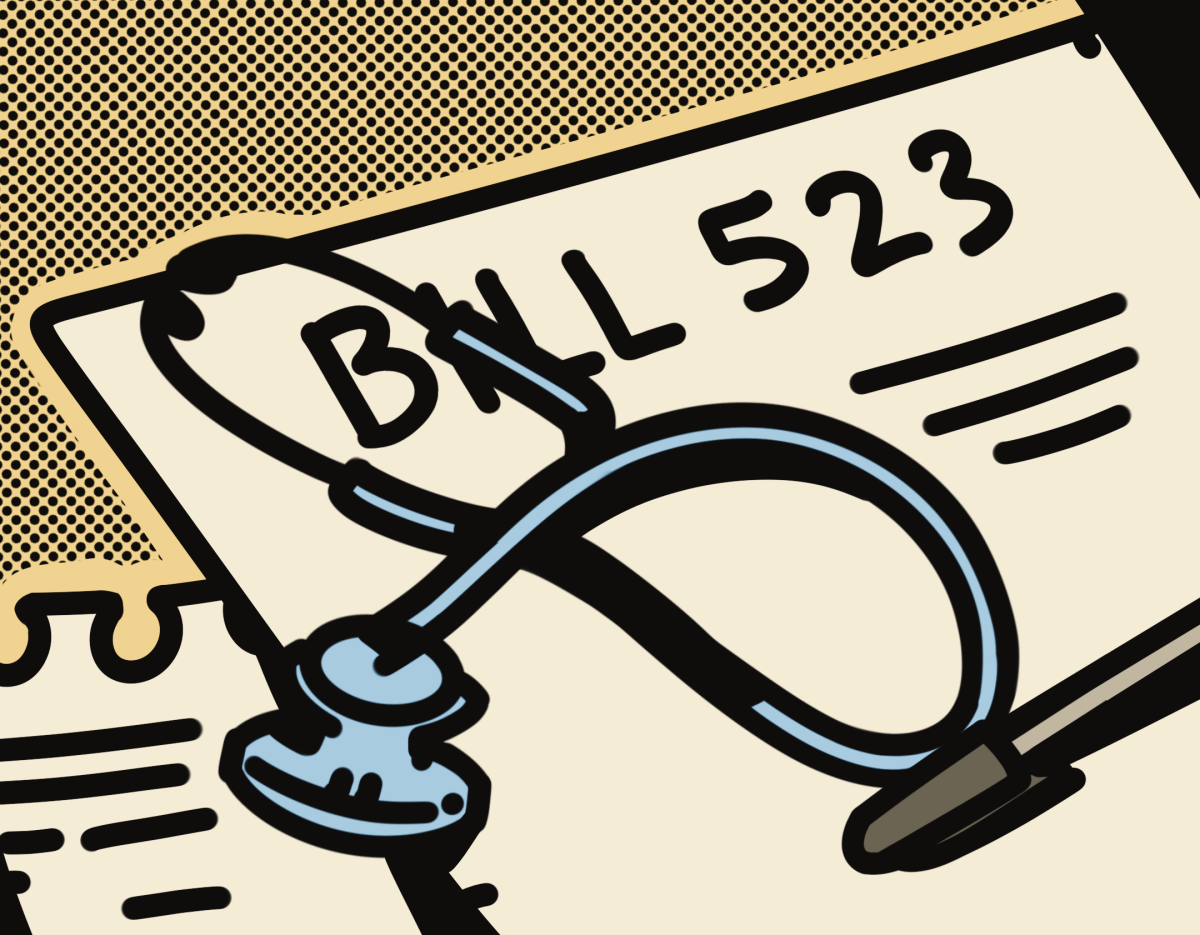

Affordable housing, as explained by McConnell, is based around Area Mean Income (AMI), or the median amount of income based on household size, as calculated by the Federal Housing Urban Development Department (HUDD). According to the HUDD, Affordable housing should not cost more than 30% of a household’s AMI.

McConnell noted that even though that should be the case, a lot of people do pay more than 30% of their income on housing.

The money that is then paid to develop that house or property has to be paid for with some form of subsidy- or government money distributed at the government’s whim. Affordable housing in Bend in particular usually requires subsidy in order to retain its affordability as well.

“In Bend you cannot build housing with the price people are able to pay with our income levels right now,” McConnell said. “That’s where subsidy comes in to make up that difference.”

McConnell explained that a lot of people in Bend do qualify for affordable housing, however, they aren’t able to produce the houses in bulk the way the community needs.

Bend’s problem is based around supply and demand- supply being housing and demand being the people of Bend. The demand is growing while the supply grows, but at a vastly inferior rate.

McConnell said that her impression of the main problem is the amount of subsidy politicians are willing to put toward this housing issue. When the subsidies aren’t coming in, the affordable housing can’t be built as they rely on those subsidies.

“In Bend, we have made a very deliberate attempt to clear as many barriers as we can for the development of true affordable housing,” McConnell said.

The love for Bend as a city is apparent and is shown in so many different ways. McConnell explained how seeing something you love change or grow is hard and it’s a natural gut reaction for people to want to resist it.

“I love this town, too,” McConnell said.

The suggestion McConnell made for the community was to do their best in accommodating the growth of this city. The state isn’t going to allow a wall to be built to keep people out nor are they going to prevent anyone from moving to Oregon.

McConnell hopes for some acceptance from the community regarding the fact Bend is going to change, and during that process, she hopes to retain the “soul of Bend.”

“The soul of Bend includes a lot of our lower wage workers; the folks serving us hamburgers, or coffee; the folks who are answering the phone when we call 911; who are taking care of us if we have a medical emergency; teachers, childcare providers; all of these folks, at one point, will qualify for affordable housing,” McConnell said.

In the process of accommodating for the growth and accepting the changes of the city, difficult though it may be, the community will be providing for the people who make our city so great.

That being said, McConnell did not deny the fact that while people move here, there is upward pressure being put on housing prices. It still came back down to a supply and demand issue; houses are simply not being built fast enough.

“Growth is a challenge, but it is also an opportunity. There are new folks around the table now talking about [affordable housing],” McConnell said.

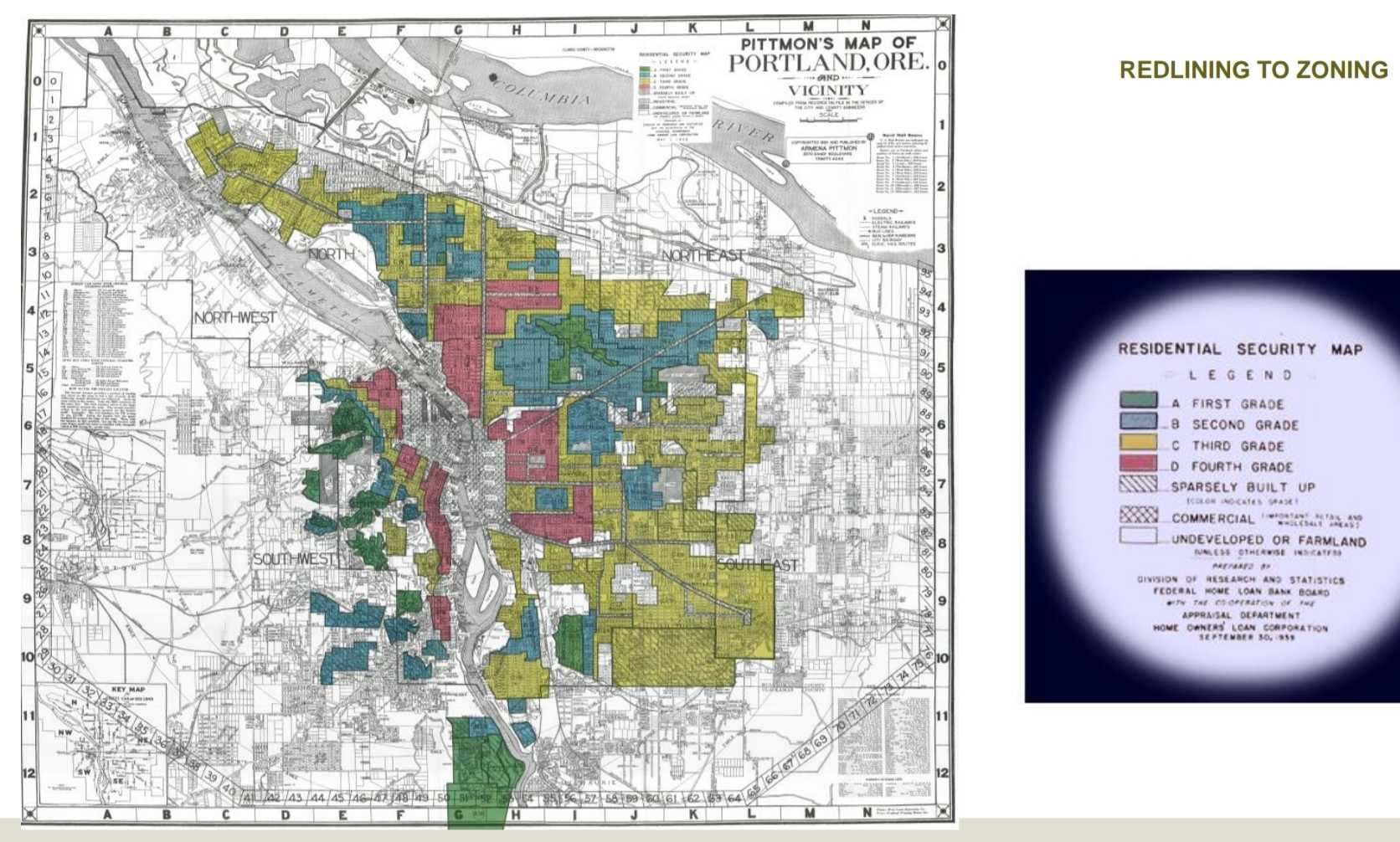

Affordable housing doesn’t just come from the average mean income rate of a city, another factor is the location of the housing unit. This locational factor, or restrictive/exclusionary zoning, came from something created by the government in the early 1900s called Redlining.

Redlining was created as a way to help people in power stay in power, by way of helping certain people live where the government wanted them to live and helping certain other people live in certain other places, specifically and typically segregated by race.

Brief history of Redlining

This created zones that were “A-Graded” all the way to “D-Graded”. A-graded zones were labeled as most favorable, and expensive, because they lacked any foreigner or African American.

Where Redlining happened was in the lowest graded zone, D-graded. This meant that there weren’t financing options available for the people in these zones to assist with purchasing land or housing leading to a steep financial and asset imbalance.

Eventually, the Supreme Court banned the use of race-based zoning, and what came from that was restrictive zoning areas. According to McConnell, there has been no debate that restrictive zoning arose from the segregation enforced by redlining.

Back to the article

Restrictive zoning acts as a barrier to simply creating more homes, as the laws surrounding them state only specific types of homes can exist in specific areas. This does not allow for diversity in income level, which directly correlates to race as McConnell also mentioned that for every one-dollar a white household has, on average, a black household has five to fourteen-cents.

One of the steps Bend has taken toward affordable housing is examining the necessity of restrictive or exclusionary zoning happening in the city.

“Most of us have no idea [redlining] is what led to zoning… We’re at the point where we’re recognizing that just because it’s been done this way for a long time, doesn’t mean this is the right way to do it,” McConnell said.

McConnell talked about how important comments from the community were to the work she and her team were doing and continue to do.

“It’s slow to get new housing on the ground and know that we’re doing everything we can. We welcome folks to look for options and call us or even email if they can’t find what they need and we’ll do what we can,” McConnell said.

That being said, she wanted to let people know her team does not do direct placement, nor do they own any property management facilities, but she encouraged people to look into other groups in the community.

A few recommendations McConnell referred to for people seeking housing assistance were Courtesy Apartment List: by Housing Works, Thrive Central Oregon, and Neighborhood Impact.

“My No. 1 advice for people is to be persistent. Get yourself on the list and call back frequently and check in and make sure you’re still on the list and that they haven’t been trying to contact you,” McConnell said, and added that there is turnover as the facilities take awhile to build and people sometimes find options faster than facilities are made.

McConnell said she felt optimistic about the community and she is aware of the struggles a lot of the residents are going through right now.

“One of the best things in the world is seeing folks move into their place for the first time, whether it’s an apartment, [or] a home, or whatever it is, and [they] recognize that this is their security and that they can engage in this community because they’ll be here. That’s a powerful thing and that’s why we do our work,” McConnell said.

The city is beginning the outreach portion of the Consolidated Plan that was launched in 2019. This was a five-year plan made for the housing department of Bend to act as a reference guide on how they spend their money.

Over the next six months there will be outreach opportunities including surveys that will be looking for opinions and ideas about housing in Bend.

McConnell encouraged students to participate in these surveys as this outreach portion will largely influence the work the housing department does moving forward.