Due to the increase in syphilis rates in Oregon, specifically in the female population because of congenital syphilis (CS), the Deschutes County Health Department suggested a decrease in stigma toward sexual and reproductive health to create a more open educational enviroment as well as focusing on inequities found within the community.

Rates and Inequities

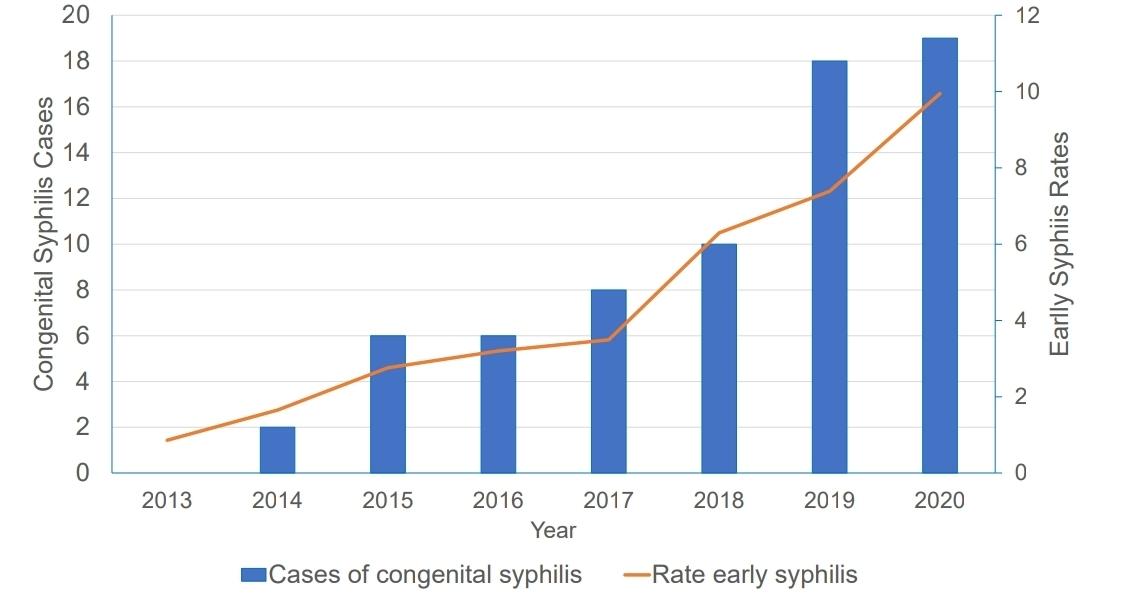

The rate of syphilis, including all levels (primary, secondary, early non-primary non-secondary syphilis) among people assigned female at birth increased over 900% from 2013 to 2020.

“The trends we’re seeing in STDs (sexually transmitted diseases) now, are really connected to social determinants of health [and] people who have inequities… It’s going to take a community to address some of those inequities that are impacting people’s health,” said Kathy Christensen, Public Health Supervisor of Deschutes County Health Department on Thursday, May 8th.

Currently, more cases are showing up in the houseless and drug-using communities across the state due to inequities and a variety of barriers to health care such as inability to even apply to insurance due to not having an address or phone number to call.

“People with inequities can be afraid to talk to providers because of previous bad experiences, so they’re less likely to go and seek help… it’s a horrible cycle,” said Public Health Nurse Amber Knapp, RN, BSN. Knapp works in the STD/HIV Program department of Deschutes County Health Services.

“It’s not just houseless folks who are getting STDs. STDs do not choose… [There are] many other folks, as well,” Christensen said.

Risks

Anyone engaging in oral, vaginal, or anal sexual activities can be at risk of syphilis. It’s spread through direct contact with a syphilitic sore, which does not always present in the same way, according to Christensen.

These sores can be anywhere, and are usually (not always) painless. The areas Knapp referred to as examples were around or on the genitals, in the mouth, and some had been seen on the belly button.

“A lot of people don’t have symptoms, so that’s an issue [too]. People can have it for a long time and have no idea, unless they go in and get testing,” Knapp said.

The majority of syphilis cases are seen in people ages 20 and up.

“[That] doesn’t mean we don’t have teens [with syphilis], in general, that’s just not the majority of cases,” Christensen said.

Partners of people-at-risk are also, by association, at risk themselves. This happens a lot according to Christensen, where one partner gets treatment for syphilis and goes back to the other partner and experiences re-exposure. This is called “treatment-failure”.

Knapp explained that part of her job and services that Deschutes County Health provides is what’s known as “partner notification”. In the event that a person does not feel comfortable telling their partner about their diagnosis, the county will reach out anonymously to let that partner know they’ve been exposed (to an STD/STI) and refer them to testing and treatment.

Safe Sex and Prevention

Proper condom-use and screening are the best prevention methods for syphilis. In a lot of cases, people will only be tested for gonorrhea and chlamydia.

“The problem is a lot of people go in and ask for STD testing and they get gonorrhea and chlamydia [testing] and they think, ‘Oh, I was tested for everything,’… Syphilis and HIV are blood-draw tests. So, just having that education to know, ‘Oh, I was tested for all these things,’ [is helpful],” Knapp said.

Being tested too early after exposure to syphilis can lead to a negative test, explained Knapp. A persistent back-and-forth between a primary care physician and their patient is vital in prevention of STDs/STIs.

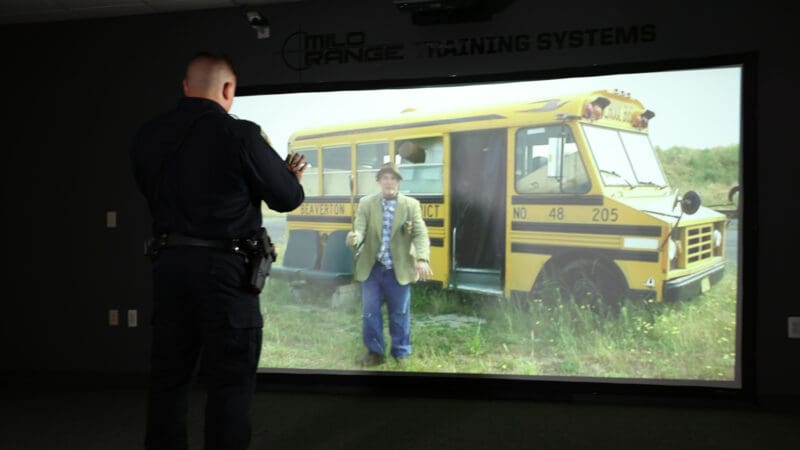

Suggested screening locations are a primary care physician’s clinic, or if symptoms are present, a person can go to urgent care. In these places, Christensen advised to be prepared to advocate for yourself.

“If you go to a Planned Parenthood or a public health clinic, [Planned Parenthood and the clinic is] going to be much more apt to ask for that kind of thing [testing],” Christensen said.

Symptoms

The symptoms can be easy to miss, especially when someone doesn’t know what to look for. Knapp and Vincent Cancelliere, STD/HIV Prevention Coordinator at Deschutes County Health Services, explained some common symptoms in syphilis, and explained what to look for.

From three weeks to three months after exposure, a person can develop a “chancre” or sore which is what health care professionals refer to as primary syphilis. This sore is usually painless, but as it is an open sore, sometimes a person can develop a secondary infection which would make it painful, Knapp said.

“The difficult thing with a lot of these symptoms is that they go away and people don’t know what they are. Some providers do not catch it,” Cancelliere said.

After the initial sore goes away, approximately 25% of people develop secondary syphilis. This often presents as a rash, which can appear anywhere on the body, commonly on the torso, but will occasionally appear on the hands, Knapp explained.

“[The rash is] not usually itchy and you can get swollen lymph nodes, or hair loss, or white patches on the mouth,” said Public Health Nurse, Charlotte Jones, RN, BSN, of Deschutes County Health Services.

Knapp went on to say that sometimes people develop new sores, or lesions, in the groin area and those are typically uncomfortable. Sometimes the sores and rashes will eventually disappear on their own and that person could just stop having any problems. Sometimes the affected person can develop neural syphilis or tertiary syphilis.

“That’s why you should always get a full screening,” Cancelliere said.

Syphilis and Congenital Syphilis

Syphilis by itself can be unnoticable. Approximately one quarter of people who get syphilis actually progress onto secondary syphilis, which has symptoms that are primarily an aesthetic annoyance rather than a painful or itchy skin condition.

The problem is congenital syphilis (CS). According to the CD Summary published in May 2021, created by the Oregon Health Authority, 7% of CS cases in Oregon from 2014 to 2020 were stillborn. 3% died in the first 28 days of life. This amounts to a 10% fatality rate for CS in Oregon from 2014 to 2020.

CS happens when a pregnant person with syphilis passes their infection to their baby during pregnancy. CS can cause miscarriage, low birth weight (No. 2 cause of infant mortality, or death, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), pre-term delivery, as well as neonatal death and stillbirth.

Infants who are born may develop bone deformities, anemia, neurologic problems, hepatosplenomegaly (swelling of liver and spleen), jaundice (stemming from liver conditions), and skin rashes.

In October 2021, the Oregon Health Authority issued a health alert via the Health Alert Network that sought to notify public health professionals about the urgent rise in congenital syphilis cases in Oregon.

“People can arm themselves with good information and advocate for themselves… Even if you don’t think for one second that you’re at risk for HIV or syphilis, it’s just good to know you don’t have it,” Christensen said.