Kirsteen Wolf

The Broadside

You depend on bees for one third of the contents of your cupboard. Without them, we would go hungry. Bees pollinate more than 90 different food crops as well as wild plants and fiber crops. Their worth is calculated at 500 million in Oregon alone and 15 billion nationwide.

But the bees are disappearing.

Close to 100 attendees came out to hear Dr. Remesh Sagili from OSU in Corvallis speak about his specialty: the health, nutrition and pollination of honey bees at the March 27 “Science Pub” lectures hosted by Oregon State University-Cascades.

“Honey bees have been taken for granted for a while,” said Sagili. “I think now they are getting the respect they deserve.”

Sagili has been passionate about bees since he was a kid. In high school, he witnessed his grandparents sunflower crop being hand pollinated after the indiscriminate use of pesticides drastically reduced the numbers of bees that used to do the job.

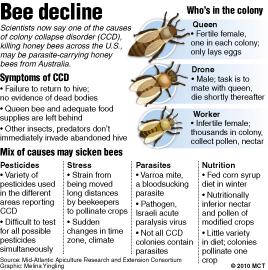

Sagili was hired at Oregon State University in March 2009 after beekeepers and farmers asked the Oregon legislature to fund honeybee research. The pressure on lawmakers resulted from panic over losing so many bees to Colony Collapse Disorder. Beginning in October 2006, some beekeepers began reporting losses of 30-90 percent of their hives according to United States Department of Agriculture. Sagili said that a 10-15 percent loss was normal.

“The main symptom of CCD is simply no or a low number of adult honey bees present but with a live queen and no dead honey bees in the hive. Often there is still honey in the hive, and immature bees (brood) are present” according to the USDA.

The worker bees just vanish.

Sagili stressed at his lecture that CCD is a set of symptoms and not a disease itself. Scientists still don’t know what is causing the loss of so many colonies. Is it nutrition? Pesticides? Fungicides? Mites? Bee rapture?

It could be all of the above (aside from the rapture), according to Sagili. From infection from the Varroa mite, poor nutrition (from bees feeding on mono crops), overcrowding, a pathogenic gut microbe called Nosema and stress from being trucked long distances, the bees immune systems might be compromised. Combine that with a lack of genetic diversity, in-hive chemicals and pesticides and fungicides and you have a web of interweaving factors that is tricky to study.

Working on a complex problem that affects a complex organism is what drives biologists. Sagili likes his work and encourages students to pursue science.

“If you have a passion for science,” said Sagili, “You should not ignore it.”

S agili earned his BA and Masters in agriculture in India and completed a PhD in entomology in Texas in 2007 just a year after the first report of CCD. Although he recognizes that science students may need to pursue advanced degrees he feels the job market is good and they will find work.

agili earned his BA and Masters in agriculture in India and completed a PhD in entomology in Texas in 2007 just a year after the first report of CCD. Although he recognizes that science students may need to pursue advanced degrees he feels the job market is good and they will find work.

“I see a bright future for science,” he said.

And with 2.5 million managed colonies in the U.S. what is the future for bees?

“With all the awareness and support for bees,” said Sagili,”I see their future as bright as well.”

(Contact: [email protected])