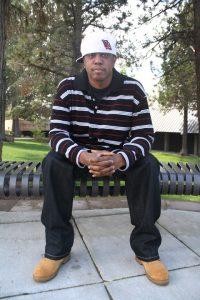

He has been pulled over by the police for looking suspicious. Women have clutched their purses when he walked by. He notices other parents don’t sit by him at his children’s school assemblies.

He notices that a lot.

Kirsteen Wolf

The Broadside

Teryl Young came to Oregon from Virginia in 2007 to help take care of his wife’s ageing parents. It was culture shock. Virginia is 19.4 percent black versus Oregon’s, 1.8 percent.

“I got the stares I wasn’t used to,” said Young.

After an incident of racial tension, Young’s first in job Oregon at a Gilchrist mill lasted one day. His wife Kim Gitchell-Young—who is white—grew up there. Despite the mill incident, living in Oregon small towns has been easier for Young and his wife than living in Bend.

In Bend, only 0.5 percent of the population is black.

Steven Jackson, a fellow Central Oregon Community College student, described it as isolating.

“Every single place I go,” he said, “I will always be the only black person there.”

Oregon has a racist history. The state ratified the 15th Amendment in 1959—89 years after black men were granted constitutional voting rights in the United States. In the mid-1800s, there was a “lash law,” where blacks were whipped if they didn’t leave the territory. As late as the 1950s, interracial marriages were still banned and non-whites were charged higher insurance rates.

Teryl Young—a COCC student—thinks these historical facts should be known if Oregonians want to move toward diversity acceptance.

“You have to know your history,” said Young.

For the Youngs, the most difficult aspects of racism involve their children.

On one occasion, Gitchell-Young caught a man taking pictures of her kids at the playground. She confronted him and told her kids to go home. As they took off, the man yelled, “Run, little niggers, run!” Young called the police and the man and his wife—who admitted using the same language—were kicked out of the apartment buildings for using hate speech.

“It felt good to get them out of there,” said Gitchell-Young, a COCC Criminal Justice major.

But the problems didn’t stop there.

Another time, a 12-year-old boy from their neighborhood told Young’s kids he could play with them, but his mother didn’t want him anywhere around Young because he was black. Young and his wife went to talk with the mother, who said she was raped by a black man and Young scared her. He responded that countless numbers of his ancestors were raped by white men and asked, “Should I hate you?”

Talking openly helped the situation and the Youngs try to be positive with the 12-year-old boy.

Steven Jackson has run into racism at COCC in his one-and-a-half years in Bend.

Last spring, Jackson’s wife was in the math lab with about seven other students. A man was talking on his cell phone using racial epithets. No one else said anything. Jackson’s wife asked that he take his call outside, saying she found his language offensive.

In response, the man said he recognized her, called her a “nigger lover” and threatened her. Someone finally came to her defense but Jackson’s wife was afraid.

Jackson feels instances like this are the exception and most people in Bend are kind. In a town with few minorities, he believes stares are inevitable.

“If you go to the beach you are going to get wet,” he said. “And we are at the beach.”

While shopping, people will stare at him. Occasionally, kids will ask to touch his skin. Jackson smiles and talks to people, though admits it sometimes gets uncomfortable—like the looks he gets when he shoots pool.

He doesn’t feel it’s his responsibility to put people at ease people, but rather to be understanding and empathetic.

“It’s not a race issue. It’s not that people are saying: ‘We hate black people,’” Jackson said. “It’s that ‘we don’t know any.’”

Explanations

Dr. Chris Wolsko’s research “explores ideas for the future as to how we get along.” An assistant professor of psychology at Oregon State University-Cascades, Wolsko studies interethnic ideology, stereotyping, racism and cross-cultural conceptions of well-being. He finds the “contact hypothesis”—the belief that exposure to a group can lessen racial ignorance—flawed.

“In general, there is a mild positive correlation between the amount of personal contact and the lessening of animosity,” said Wolsko.

He cited states with intense racial conflict despite daily exposure between different groups. Young said there was “in-your-face racism” back in Virginia Beach.

“Just because you have contact doesn’t mean you will get along,” said Wolsko.

There are many theories explaining why hostilities exist between groups. Wolsko outlined a few psychological explanations for Young and Jackson’s negative experiences in Bend, including:

Negative stereotypes from mainstream media

Preexistent socioeconomic status difference

Historical conflict between groups

Ignorance

Negative direct experience

If any stereotype forms in a person’s mind, they can potentially view someone from that group as a threat. People might look at a person and place him or her in a category without being aware of their thought processes, said Wolsko.

The Black Student Union

“There is no support in Bend. No support,” said Jackson. “You are an island.”

When asked what advice he would offer a new black student, Jackson was quick to respond.

“Go find Gordon Price,” he said.

Price is the Director of Student Life at COCC. He understands the challenges of being black in Bend. Price recalls an incident during a college orientation. He stood in front of 150 high school students, talking about college life and offering encouragement while they restlessly shuffled their folders of paper. After they filed out, Price found several folders left behind on the floor with the words “kill all the niggers” scribbled on them.

“Sometimes you can get lulled into complacency when things don’t happen for a while,” Price said. “Then you get reminders that racism is still out there.”

Price is also the advisor to the Black Student Union, a COCC club.

The BSU formed as a network and support system for African American students. The club was envisioned as a place to share stories, communicate and combat the isolation that African Americans and their families feel in Bend and on campus, said Price. As part of his job, Price receives the names of anyone who self-identifies as African American. In winter term, that number—out of more than 10,000 credit students—was 54.

It’s not a lot, but it’s enough to form a club. Sporadic leadership, lack of cohesion and poor event attendance, however, has made it difficult to keep the BSU going. Price hopes to try again next fall.

“I need student support to keep it going,” he said.

Teaching Diversity

Bend is 91 percent white. So what can people do to prevent racial conflicts so Young, Jackson and Price’s experiences are not an expected part of being black in Bend?

“The first level is to make people aware of what is going on in their minds,” said Chris Wolsko.

People draw boundaries between groups and express different priorities—it’s the nature of groups. Wolsko feels that an open dialogue and an awareness of diversity is a way to reach another level of understanding.

“We need managed conflict,” he said.

Steven Jackson hopes people become more receptive to diversity. But how do you teach diversity to a predominantly white town?

If learning about diversity is not personal, said Jackson, most people won’t care. He concedes that learning about the issues makes a difference.

“It’s education,” he said. “It has to matter.”

Finding diversity

Young’s experience as a Central Oregon black man made sense to him after attending the lecture “Hidden History: Why Aren’t There More Black People in Oregon?” by speaker Walidah Imarisha at the COCC campus, on April 10.

Imarisha moved from Philadelphia—43 percent black—to Portland, a city with a 6.3 percent black population. She found ways to adjust.

“It was important for me to think ahead and be very intentional … about reaching out to organizations, communities and institutions where I would find people of color, and folks who were thinking about issues of justice and equity,” she said.

Such a place exists in the Multicultural Activities department at COCC. Director Karen Roth has hosted more than 40 events this school year that explore topics ranging from transgender issues to immigrant rights.

The motivation behind the Multicultural Activities department was to make staff and faculty members aware of ways they may be acting on their unconscious biases.

The subtle ways that ostracize minorities—looks on campus, being ignored, clutched purses— are called “micro aggressions” according to Roth. If you’re not on the receiving end of these aggressions, chances are you might not be aware of them.

“We have to help them understand that all people of color are experiencing micro aggressions,” said Roth.

With the job situation in Bend, Young recognizes most graduates will have to move to more racially diverse places. Students should attend classes and lectures to understand how they personally deal with other races, he suggested.

“If you don’t talk about it,” said Young.” You can’t fix it.”

(Contact: [email protected])